What is Legionnaire's disease?

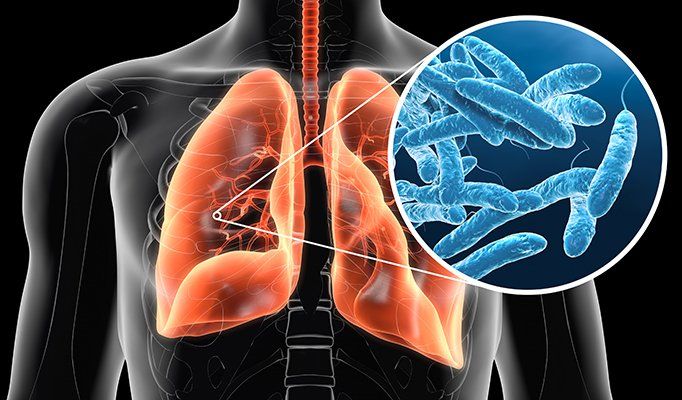

A potentially fatal form of pneumonia. Everyone is susceptible to legionella infection. It can cause long term health problems and, in rare cases, death.

If you are an employer or someone in control of premises (such as a landlord), you have a duty to understand and manage legionella risks. This is where our training courses come in.

Key facts

The bacterium Legionella pneumophila was first identified in 1977, as the cause of an outbreak of severe pneumonia in a convention centre in the USA in 1976.

The most common form of transmission of Legionella is inhalation of contaminated aerosols produced in conjunction with water sprays, jets, or mists. Infection can also occur by aspiration of contaminated water or ice, particularly in susceptible hospital patients.

Legionnaires’ disease has an incubation period of 2 to 10 days (but up to 16 days has been recorded).

Death occurs through progressive pneumonia with respiratory failure and/or shock and multi-organ failure.

Untreated Legionnaires’ disease usually worsens during the first week.

Of the reported cases 75–80% are over 50 years and 60–70% are male.

World Health Organisation Legionella Information 2020

Legionellosis varies in severity from a mild febrile illness to a serious and sometimes fatal form of pneumonia and is caused by exposure to Legionella species found in water, and potting mixes.

It is often categorized as being community, travel or hospital acquired based on the type of exposure.

Worldwide, waterborne Legionella pneumophila is the most common cause of cases including outbreaks. Legionella pneumophila and related species are commonly found in lakes, rivers, creeks, hot springs, and other bodies of water. Other species including L. longbeachae can be found in potting mixes.

The bacterium L. pneumophila was first identified in 1977, as the cause of an outbreak of severe pneumonia in a convention centre in the USA in 1976. It has since been associated with outbreaks linked to poorly maintained artificial water systems, particularly cooling towers or evaporative condensers associated with air conditioning and industrial cooling, hot and cold-water systems in public and private buildings, and whirlpool spas.

The infective dose is unknown but can be assumed to be low for susceptible people, as illnesses have occurred after short exposures and 3 or more km from the source of outbreaks. The likelihood of illness depends on the concentrations of Legionella in the water source, the production and dissemination of aerosols, host factors such as age and pre-existing health conditions and the virulence of the strain of Legionella. Most infections do not cause illness.

-

The cause

The causative agents are Legionella from water or potting mix. The most common cause of illness is the freshwater species L. pneumophila which is found in natural aquatic environments worldwide. However, artificial water systems which provide environments conducive to the growth and dissemination of Legionella represent the most likely sources of disease.

The bacteria live in water systems at temperatures of 20 to 50 degrees Celsius (optimal 37 degrees Celsius). Legionella can survive and grow as parasites within free-living protozoa and within biofilms which develop in water systems. They can cause infections by infecting human cells using a similar mechanism to that used to infect protozoa.

-

Transmission

The most common form of transmission of Legionella is inhalation of contaminated aerosols. Sources of aerosols that have been linked with transmission of Legionella include air conditioning cooling towers, hot and cold-water systems, humidifiers, and whirlpool spas. Infection can also occur by aspiration of contaminated water or ice, particularly in susceptible hospital patients, and during water births. There is no direct human-to-human transmission.

-

Distribution

Legionnaires’ disease is believed to occur worldwide.

-

Extent of the disease

The identified incidence of Legionnaires’ disease varies widely according to the level of surveillance and reporting. Since many countries lack appropriate methods of diagnosing the infection or sufficient surveillance systems, the rate of occurrence is unknown. In Europe, Australia, and the USA there are about 10–15 cases detected per million population per year.

Of the reported cases 75–80% are over 50 years and 60–70% are male. Other risk factors for community-acquired and travel-associated legionellosis include smoking, a history of heavy drinking, pulmonary-related illness, immuno-suppression, and chronic respiratory or renal illnesses.

Risk factors for hospital-acquired pneumonia are recent surgery, intubation, which is the process of placing a tube in the trachea, mechanical ventilation, aspiration, presence of nasogastric tubes, and the use of respiratory therapy equipment. The most susceptible hosts are immuno-compromised patients, including organ transplant recipients and cancer patients and those receiving corticosteroid treatment.

Delay in diagnosis and administration of appropriate antibiotic treatment, increasing age and presence of co-existing diseases are predictors of death from Legionnaires’ disease.

-

Symptoms

Legionellosis is a generic term describing the pneumonic and non-pneumonic forms of infection with Legionella.

The non-pneumonic form (Pontiac disease) is an acute, self-limiting influenza-like illness usually lasting 2–5 days. The incubation period is from a few and up to 48 hours. The main symptoms are fever, chills, headache, malaise, and muscle pain (myalgia). No deaths are associated with this type of infection.

Legionnaires’ disease, the pneumonic form, has an incubation period of 2 to 10 days (but up to 16 days has been recorded in some outbreaks). Initially, symptoms are fever, loss of appetite, headache, malaise, and lethargy. Some patients may also have muscle pain, diarrhoea, and confusion. There is also usually an initial mild cough, but as many as 50% of patients can present phlegm. Blood-streaked phlegm or haemoptysis occurs in about one-third of the patients. The severity of disease ranges from a mild cough to a rapidly fatal pneumonia. Death occurs through progressive pneumonia with respiratory failure and/or shock and multi-organ failure.

Untreated Legionnaires’ disease usually worsens during the first week. In common with other risk factors causing severe pneumonia, the most frequent complications of legionellosis are respiratory failure, shock and acute kidney and multi-organ failure. Recovery always requires antibiotic treatment, and is usually complete, after several weeks or months. In rare occasions, severe progressive pneumonia or ineffective treatment for pneumonia can result in brain sequelae.

The death rate as a result of Legionnaires’ disease depends on: the severity of the disease, the appropriateness of initial anti-microbial treatment, the setting where legionella was acquired, and host factors (for example, the disease is usually more serious in patients with immuno-suppression). The death rate may be as high as 40–80%in untreated immuno-suppressed patients and can be reduced to 5–30% through appropriate case management and depending on the severity of the clinical signs and symptoms. Overall, the death rate is usually within the range of 5–10%.

-

Response

There is no vaccine currently available for Legionnaires’ disease.

The nonpneumonic form of infection is self-limiting and does not require medical interventions, including antibiotic treatment. Patients with Legionnaires’ disease always require antibiotic treatment following diagnosis.

The public health threat posed by legionellosis can be addressed by implementing water safety plans by authorities responsible for building safety or water system safety. These plans must be specific to the building or water system and should result in the introduction and regular monitoring of control measures against identified risks including Legionella. Although it is not always possible to eradicate the source of infection, it is possible to reduce the risks substantially.

Prevention of Legionnaires’ disease depends on applying control measures to minimise the growth of Legionella and dissemination of aerosols. These measures include good maintenance of devices, including regular cleaning and disinfection and applying other physical (temperature) or chemical measures (biocide) to minimize growth. Some examples are:

- the regular maintenance, cleaning, and disinfection of cooling towers together with frequent or continuous addition of biocides.

- installation of drift eliminators to reduce dissemination of aerosols from cooling towers.

- maintaining an adequate level of a biocide such as chlorine in a spa pool along with a complete drain and clean of the whole system at least weekly.

- keeping hot and cold-water systems clean and either keeping the hot water above 50 °C (which requires water leaving the heating unit to be at or above 60 °C) and the cold below 20 °C or alternatively treating them with a suitable biocide to limit growth, particularly in hospitals and other health care settings, and aged-care facilities.

- reducing stagnation by flushing unused taps in buildings on a weekly basis.

Applying such controls will greatly reduce the risk of Legionella contamination and prevent the occurrence of sporadic cases and outbreaks. Extra precautions may be required for water and ice provided to highly susceptible patients in hospitals including those at risk of aspiration (for example, ice machines can be a source of Legionella and should not be used by highly susceptible patients). Control and prevention measures must be accompanied by proper vigilance on the part of general practitioners and community health services for the detection of cases.

NHS Legionella Information 2020

Legionnaires' disease is a lung infection you can catch by inhaling droplets of water from things like air conditioning or hot tubs. It is uncommon but can be very serious.

How you get Legionnaires' disease?

You can catch Legionnaires' disease if you breathe in tiny droplets of water containing bacteria that cause the infection.

It is usually caught in places like hotels, hospitals or offices where the bacteria have got into the water supply. It is very rare to catch it at home.

You can catch it from things like:

air conditioning systems (associated with cooling towers)

spa pools and hot tubs

showers, taps and toilets

You may need to go into hospital if you are diagnosed with Legionnaires' disease. Treatment in hospital may include:

Treatment for Legionnaires' disease:

antibiotics directly into a vein

oxygen through a face mask or tubes in your nose

a machine to help you breathe

When you start to get better you might be able to take antibiotic tablets at home. Antibiotic treatment usually lasts 1 to 3 weeks. Most people make a full recovery, but it might take a few weeks to feel back to normal.

You cannot usually get it from:

drinking water containing the bacteria

other people with the infection

places like ponds, lakes, and rivers

Legionellosis varies in severity from a mild febrile illness to a serious and sometimes fatal form of pneumonia and is caused by exposure to Legionella species found in water, and potting mixes.

Health and Safety Executive Legionella Information 2020

Introduction

Legionellosis is a collective term for diseases caused by legionella bacteria including the most serious Legionnaires’ disease, as well as the similar but less serious conditions of Pontiac fever and Lochgoilhead fever. Legionnaires’ disease is a potentially fatal form of pneumonia and everyone is susceptible to infection. The risk increases with age, but some people are at higher risk including:

people over 45 years of age

smokers and heavy drinkers

people suffering from chronic respiratory or kidney disease

diabetes, lung, and heart disease

anyone with an impaired immune system

The bacterium Legionella pneumophila and related bacteria are common in natural water sources such as rivers, lakes, and reservoirs, but usually in low numbers. They may also be found in purpose-built water systems such as cooling towers, evaporative condensers, hot and cold-water systems, and spa pools.

-

Where does it come from?

If conditions are favourable, the bacteria may grow increasing the risks of Legionnaires’ disease and it is therefore important to control the risks by introducing appropriate measures outlined in Legionnaires' disease - The Control of Legionella bacteria in water systems (L8), available at this link: https://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/books/l8.htm

Legionella bacteria are widespread in natural water systems, e.g. rivers and ponds.

However, the conditions are rarely right for people to catch the disease from these sources. Outbreaks of the illness occur from exposure to legionella growing in purpose-built systems where water is maintained at a temperature high enough to encourage growth, e.g. cooling towers, evaporative condensers, hot and cold water systems and spa pools used in all sorts of premises (work and domestic).

-

How do people get it?

People contract Legionnaires’ disease by inhaling small droplets of water (aerosols), suspended in the air, containing the bacteria. Certain conditions increase the risk from legionella if:

the water temperature in all or some parts of the system may be between 20-45 °C, which is suitable for growth

- it is possible for breathable water droplets to be created and dispersed e.g. aerosol created by a cooling tower, or water outlets

- water is stored and/or re-circulated

- there are deposits that can support bacterial growth providing a source of nutrients for the organism e.g. rust, sludge, scale, organic matter, and biofilms

Cases of Legionnaires’ disease are often the result of infections caught in the UK, but several cases occur abroad.

Useful advice on travel can be found from the

European Working Group for Legionella Infections at this link: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/european-technical-guidelines-prevention-control-and-investigation-infections

-

What are the symptoms?

The symptoms of Legionnaires' disease are like the symptoms of the flu:

• high temperature, feverishness, and chills.

• cough.

• muscle pains.

• headache; and leading on to pneumonia

• very occasionally diarrhoea and signs of mental confusion

Legionnaires’ disease is not known to spread from person to person.

How is it treated?

The illness is treated with an antibiotic called erythromycin or a similar antibiotic.

-

What to do?

If you develop the above symptoms and you are worried that it might be Legionnaires' disease, see your general practitioner.

It is not always easy to diagnose because it is like the flu. A urine or blood test will be helpful in deciding whether an illness is Legionnaires' disease or not. When doctors are aware that the illness is present in the local community, they have a much better chance of diagnosing it earlier.

If you suspect that your illness is because of your work then you should report this to your manager, as well as your health and safety representative and occupational health department, if you have one. There is a legal requirement for employers to report cases of Legionnaires' disease that may be acquired at their premises to the Health and Safety Executive.

-

Are there Legionella risks in my workplace?

Any water system, with the right environmental conditions, could be a source for legionella bacteria growth. There is a reasonably foreseeable legionella risk if your water system:

- has a water temperature between 20–45 °C

- creates and/or spreads breathable droplets, e.g. aerosol created by a cooling tower, or water outlets

- stores and/or re-circulates water

- likely to contain a source of nutrients for the organism to grow, e.g. rust, sludge, scale, organic matter, and biofilms

The most common sources of legionella are in man-made water systems including:

- cooling tower and evaporative condensers

- hot and cold-water systems

- spa pools

There are also several other potential risk systems that may pose a risk to exposure to legionella, e.g. humidifiers, air washers, emergency showers, indoor ornamental fountains etc.

If you are an employer, or someone in control of premises (e.g. landlord), you have a duty to understand and manage legionella risks. All systems require a risk assessment but not all systems will require elaborate control measures. A simple risk assessment may show that the risks are low and being properly managed to comply with the law. If such cases, your assessment may be complete and you may not need to take any further action, but it is important to review your assessment regularly in case anything changes in your system.

Visit the NHS website to read their page of information in full:

More detailed advice on legionella is available from the UK Government, Public Health England, and the Health and Safety Executive.

Please follow the links below to access more information from these bodies.

GOV.UK and Public Health England

Legionnaires' disease: guidance, data, and analysis. The symptoms, diagnosis, management, surveillance, and epidemiology of Legionnaires' disease

HSE Downloads

Legionnaires' disease. The control of legionella bacteria in water systems. Approved Code of Practice and guidance

HSE Downloads

Legionnaires' disease

A brief guide for dutyholders

World Health Organisation Legionella Information 2020

Key facts

The bacterium Legionella pneumophila was first identified in 1977, as the cause of an outbreak of severe pneumonia in a convention centre in the USA in 1976.

The most common form of transmission of Legionella is inhalation of contaminated aerosols produced in conjunction with water sprays, jets, or mists. Infection can also occur by aspiration of contaminated water or ice, particularly in susceptible hospital patients.

Legionnaires’ disease has an incubation period of 2 to 10 days (but up to 16 days has been recorded).

Death occurs through progressive pneumonia with respiratory failure and/or shock and multi-organ failure.

Untreated Legionnaires’ disease usually worsens during the first week.

Of the reported cases 75–80% are over 50 years and 60–70% are male.

Legionellosis varies in severity from a mild febrile illness to a serious and sometimes fatal form of pneumonia and is caused by exposure to Legionella species found in water, and potting mixes.

It is often categorized as being community, travel or hospital acquired based on the type of exposure.

Worldwide, waterborne Legionella pneumophila is the most common cause of cases including outbreaks. Legionella pneumophila and related species are commonly found in lakes, rivers, creeks, hot springs, and other bodies of water. Other species including L. longbeachae can be found in potting mixes.

The bacterium L. pneumophila was first identified in 1977, as the cause of an outbreak of severe pneumonia in a convention centre in the USA in 1976. It has since been associated with outbreaks linked to poorly maintained artificial water systems, particularly cooling towers or evaporative condensers associated with air conditioning and industrial cooling, hot and cold-water systems in public and private buildings, and whirlpool spas.

The infective dose is unknown but can be assumed to be low for susceptible people, as illnesses have occurred after short exposures and 3 or more km from the source of outbreaks. The likelihood of illness depends on the concentrations of Legionella in the water source, the production and dissemination of aerosols, host factors such as age and pre-existing health conditions and the virulence of the strain of Legionella. Most infections do not cause illness.

-

The cause

The causative agents are Legionella from water or potting mix. The most common cause of illness is the freshwater species L. pneumophila which is found in natural aquatic environments worldwide. However, artificial water systems which provide environments conducive to the growth and dissemination of Legionella represent the most likely sources of disease.

The bacteria live in water systems at temperatures of 20 to 50 degrees Celsius (optimal 37 degrees Celsius). Legionella can survive and grow as parasites within free-living protozoa and within biofilms which develop in water systems. They can cause infections by infecting human cells using a similar mechanism to that used to infect protozoa.

-

Transmission

The most common form of transmission of Legionella is inhalation of contaminated aerosols. Sources of aerosols that have been linked with transmission of Legionella include air conditioning cooling towers, hot and cold-water systems, humidifiers, and whirlpool spas. Infection can also occur by aspiration of contaminated water or ice, particularly in susceptible hospital patients, and during water births. There is no direct human-to-human transmission.

-

Distribution

Legionnaires’ disease is believed to occur worldwide.

-

Extent of the disease

The identified incidence of Legionnaires’ disease varies widely according to the level of surveillance and reporting. Since many countries lack appropriate methods of diagnosing the infection or sufficient surveillance systems, the rate of occurrence is unknown. In Europe, Australia, and the USA there are about 10–15 cases detected per million population per year.

Of the reported cases 75–80% are over 50 years and 60–70% are male. Other risk factors for community-acquired and travel-associated legionellosis include smoking, a history of heavy drinking, pulmonary-related illness, immuno-suppression, and chronic respiratory or renal illnesses.

Risk factors for hospital-acquired pneumonia are recent surgery, intubation, which is the process of placing a tube in the trachea, mechanical ventilation, aspiration, presence of nasogastric tubes, and the use of respiratory therapy equipment. The most susceptible hosts are immuno-compromised patients, including organ transplant recipients and cancer patients and those receiving corticosteroid treatment.

Delay in diagnosis and administration of appropriate antibiotic treatment, increasing age and presence of co-existing diseases are predictors of death from Legionnaires’ disease.

-

Symptoms

Legionellosis is a generic term describing the pneumonic and non-pneumonic forms of infection with Legionella.

The non-pneumonic form (Pontiac disease) is an acute, self-limiting influenza-like illness usually lasting 2–5 days. The incubation period is from a few and up to 48 hours. The main symptoms are fever, chills, headache, malaise, and muscle pain (myalgia). No deaths are associated with this type of infection.

Legionnaires’ disease, the pneumonic form, has an incubation period of 2 to 10 days (but up to 16 days has been recorded in some outbreaks). Initially, symptoms are fever, loss of appetite, headache, malaise, and lethargy. Some patients may also have muscle pain, diarrhoea, and confusion. There is also usually an initial mild cough, but as many as 50% of patients can present phlegm. Blood-streaked phlegm or haemoptysis occurs in about one-third of the patients. The severity of disease ranges from a mild cough to a rapidly fatal pneumonia. Death occurs through progressive pneumonia with respiratory failure and/or shock and multi-organ failure.

Untreated Legionnaires’ disease usually worsens during the first week. In common with other risk factors causing severe pneumonia, the most frequent complications of legionellosis are respiratory failure, shock and acute kidney and multi-organ failure. Recovery always requires antibiotic treatment, and is usually complete, after several weeks or months. In rare occasions, severe progressive pneumonia or ineffective treatment for pneumonia can result in brain sequelae.

The death rate as a result of Legionnaires’ disease depends on: the severity of the disease, the appropriateness of initial anti-microbial treatment, the setting where legionella was acquired, and host factors (for example, the disease is usually more serious in patients with immuno-suppression). The death rate may be as high as 40–80%in untreated immuno-suppressed patients and can be reduced to 5–30% through appropriate case management and depending on the severity of the clinical signs and symptoms. Overall, the death rate is usually within the range of 5–10%.

-

Response

There is no vaccine currently available for Legionnaires’ disease.

The nonpneumonic form of infection is self-limiting and does not require medical interventions, including antibiotic treatment. Patients with Legionnaires’ disease always require antibiotic treatment following diagnosis.

The public health threat posed by legionellosis can be addressed by implementing water safety plans by authorities responsible for building safety or water system safety. These plans must be specific to the building or water system and should result in the introduction and regular monitoring of control measures against identified risks including Legionella. Although it is not always possible to eradicate the source of infection, it is possible to reduce the risks substantially.

Prevention of Legionnaires’ disease depends on applying control measures to minimise the growth of Legionella and dissemination of aerosols. These measures include good maintenance of devices, including regular cleaning and disinfection and applying other physical (temperature) or chemical measures (biocide) to minimize growth. Some examples are:

- the regular maintenance, cleaning, and disinfection of cooling towers together with frequent or continuous addition of biocides.

- installation of drift eliminators to reduce dissemination of aerosols from cooling towers.

- maintaining an adequate level of a biocide such as chlorine in a spa pool along with a complete drain and clean of the whole system at least weekly.

- keeping hot and cold-water systems clean and either keeping the hot water above 50 °C (which requires water leaving the heating unit to be at or above 60 °C) and the cold below 20 °C or alternatively treating them with a suitable biocide to limit growth, particularly in hospitals and other health care settings, and aged-care facilities.

- reducing stagnation by flushing unused taps in buildings on a weekly basis.

Applying such controls will greatly reduce the risk of Legionella contamination and prevent the occurrence of sporadic cases and outbreaks. Extra precautions may be required for water and ice provided to highly susceptible patients in hospitals including those at risk of aspiration (for example, ice machines can be a source of Legionella and should not be used by highly susceptible patients). Control and prevention measures must be accompanied by proper vigilance on the part of general practitioners and community health services for the detection of cases.

NHS Legionella Information 2020

Legionnaires' disease is a lung infection you can catch by inhaling droplets of water from things like air conditioning or hot tubs. It is uncommon but can be very serious.

How you get Legionnaires' disease?

You can catch Legionnaires' disease if you breathe in tiny droplets of water containing bacteria that cause the infection.

It is usually caught in places like hotels, hospitals or offices where the bacteria have got into the water supply. It is very rare to catch it at home.

You may need to go into hospital if you are diagnosed with Legionnaires' disease. Treatment in hospital may include:

Treatment for Legionnaires' disease:

antibiotics directly into a vein

oxygen through a face mask or tubes in your nose

a machine to help you breathe

When you start to get better you might be able to take antibiotic tablets at home. Antibiotic treatment usually lasts 1 to 3 weeks. Most people make a full recovery, but it might take a few weeks to feel back to normal.

You can catch it from things like:

air conditioning systems (associated with cooling towers)

spa pools and hot tubs

showers, taps and toilets

You cannot usually get it from:

drinking water containing the bacteria

other people with the infection

places like ponds, lakes, and rivers

Legionellosis varies in severity from a mild febrile illness to a serious and sometimes fatal form of pneumonia and is caused by exposure to Legionella species found in water, and potting mixes.

Health and Safety Executive Legionella Information 2020

Introduction

Legionellosis is a collective term for diseases caused by legionella bacteria including the most serious Legionnaires’ disease, as well as the similar but less serious conditions of Pontiac fever and Lochgoilhead fever. Legionnaires’ disease is a potentially fatal form of pneumonia and everyone is susceptible to infection. The risk increases with age, but some people are at higher risk including:

people over 45 years of age

smokers and heavy drinkers

people suffering from chronic respiratory or kidney disease

diabetes, lung, and heart disease

anyone with an impaired immune system

The bacterium Legionella pneumophila and related bacteria are common in natural water sources such as rivers, lakes, and reservoirs, but usually in low numbers. They may also be found in purpose-built water systems such as cooling towers, evaporative condensers, hot and cold-water systems, and spa pools.

-

Where does it come from?

If conditions are favourable, the bacteria may grow increasing the risks of Legionnaires’ disease and it is therefore important to control the risks by introducing appropriate measures outlined in Legionnaires' disease - The Control of Legionella bacteria in water systems (L8), available at this link: https://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/books/l8.htm

Legionella bacteria are widespread in natural water systems, e.g. rivers and ponds.

However, the conditions are rarely right for people to catch the disease from these sources. Outbreaks of the illness occur from exposure to legionella growing in purpose-built systems where water is maintained at a temperature high enough to encourage growth, e.g. cooling towers, evaporative condensers, hot and cold water systems and spa pools used in all sorts of premises (work and domestic).

-

How do people get it?

People contract Legionnaires’ disease by inhaling small droplets of water (aerosols), suspended in the air, containing the bacteria. Certain conditions increase the risk from legionella if:

the water temperature in all or some parts of the system may be between 20-45 °C, which is suitable for growth

- it is possible for breathable water droplets to be created and dispersed e.g. aerosol created by a cooling tower, or water outlets

- water is stored and/or re-circulated

- there are deposits that can support bacterial growth providing a source of nutrients for the organism e.g. rust, sludge, scale, organic matter, and biofilms

Cases of Legionnaires’ disease are often the result of infections caught in the UK, but several cases occur abroad.

Useful advice on travel can be found from the

European Working Group for Legionella Infections at this link: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/european-technical-guidelines-prevention-control-and-investigation-infections

-

What are the symptoms?

The symptoms of Legionnaires' disease are like the symptoms of the flu:

• high temperature, feverishness, and chills.

• cough.

• muscle pains.

• headache; and leading on to pneumonia

• very occasionally diarrhoea and signs of mental confusion

Legionnaires’ disease is not known to spread from person to person.

How is it treated?

The illness is treated with an antibiotic called erythromycin or a similar antibiotic.

-

What to do?

If you develop the above symptoms and you are worried that it might be Legionnaires' disease, see your general practitioner.

It is not always easy to diagnose because it is like the flu. A urine or blood test will be helpful in deciding whether an illness is Legionnaires' disease or not. When doctors are aware that the illness is present in the local community, they have a much better chance of diagnosing it earlier.

If you suspect that your illness is because of your work then you should report this to your manager, as well as your health and safety representative and occupational health department, if you have one. There is a legal requirement for employers to report cases of Legionnaires' disease that may be acquired at their premises to the Health and Safety Executive.

-

Are there Legionella risks in my workplace?

Any water system, with the right environmental conditions, could be a source for legionella bacteria growth. There is a reasonably foreseeable legionella risk if your water system:

- has a water temperature between 20–45 °C

- creates and/or spreads breathable droplets, e.g. aerosol created by a cooling tower, or water outlets

- stores and/or re-circulates water

- likely to contain a source of nutrients for the organism to grow, e.g. rust, sludge, scale, organic matter, and biofilms

The most common sources of legionella are in man-made water systems including:

- cooling tower and evaporative condensers

- hot and cold-water systems

- spa pools

There are also several other potential risk systems that may pose a risk to exposure to legionella, e.g. humidifiers, air washers, emergency showers, indoor ornamental fountains etc.

If you are an employer, or someone in control of premises (e.g. landlord), you have a duty to understand and manage legionella risks. All systems require a risk assessment but not all systems will require elaborate control measures. A simple risk assessment may show that the risks are low and being properly managed to comply with the law. If such cases, your assessment may be complete and you may not need to take any further action, but it is important to review your assessment regularly in case anything changes in your system.

Visit the NHS website to read their page of information in full:

More detailed advice on legionella is available from the UK Government, Public Health England, and the Health and Safety Executive.

Please follow the links below to access more information from these bodies.

GOV.UK and Public Health England

Legionnaires' disease: guidance, data, and analysis. The symptoms, diagnosis, management, surveillance, and epidemiology of Legionnaires' disease

HSE Downloads

Legionnaires' disease. The control of legionella bacteria in water systems. Approved Code of Practice and guidance

HSE Downloads

Legionnaires' disease

A brief guide for dutyholders

Any Questions?

CALL 0115 784 3100 - OUR LINES ARE OPEN MON TO FRI, 8AM-5PM

OR EMAIL response@secondelement.org.uk

Second Element’s Legionella Training Courses

TRAINING COURSE - DURATION 1 HOUR

LEGIONELLA AWARENESS

Designed for people:

Who have no legionella experience.

Are involved with a legionella control regime who do not have overall responsibility.

- Understand the risks from legionella bacteria and legionnaires disease

- Understand the legal requirements of legionella control

- Understand legionella control in hot and cold water systems

- Understand how to keep water systems safe

TRAINING COURSE - DURATION 3 HOURS

ROLE OF THE RESPONSIBLE PERSON

Designed for people:

In charge of premises (The Duty Holder).

In charge of the legionella control regime (The Responsible Person).

- Understand what a Duty Holder and Responsible Person is accountable for

- Includes legionella awareness refresher

- Overview of ACoPL8, HSG274 Parts 2 and 3

- Allocation of legionella control tasks, communication and escalation

- Understanding Legionella Risk Assessments, schematic drawings and prioritising actions

- Record Keeping

- Know what to do when things go wrong. Legionella positives and cases of legionnaires’ disease.

- Avoiding deadly blunders